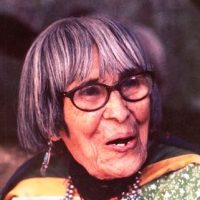

Few craft artists, Native American or otherwise, can claim worldwide fame and appreciation, but these accompanied the life of potter Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo. Through her hard work and generous sharing of her techniques, Maria reintroduced the art of pottery making to her people, providing them with a means of artistic expression and for retaining some aspects of the pueblo way of life.

San Ildefonso Pueblo is a quiet community located 20 miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Inhabited since A.D. 1300, the pueblo saw many changes that resulted in a rich culture, in which ancient traditions mix with Spanish festivals and Anglo conveniences. Life in the Tewa-speaking village on the Pajarito Plateau is filled with love for one’s neighbor and respect for the God-given gifts of the earth. Into this community, at a time of great transition from isolation to increased contact with other peoples, Maria Antonia Montoya was born, probably in the year 1887. For nearly one hundred years, until her death in 1980, Maria lived in the pueblo, eager to greet visitors and to share her craft with those who would like to watch and listen.

Maria’s fascination with pottery-making started at a young age, when she would watch her aunt making pots, after her chores were done. Although many women in the pueblo knew how to make pottery, by Maria’s time it was no longer a necessary part of daily life. Inexpensive Spanish tinware and Anglo enamelware had replaced traditional containers and cooking pots. In many ways, the art of pottery making was facing extinction. Fortunately, Maria’s interest and willingness to experiment with techniques prevented this from occurring.

Not long after her marriage to Julian Martinez, Maria was asked to replicate some pre-historic pottery styles that had been discovered in an archaeological excavation of an ancient pueblo site near San Ildefonso. These excavations of 1908 and 1909, led by Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett (who was also the director of the Museum of New Mexico), produced examples of many pre-historic pottery techniques. Dr. Hewett asked Maria, who already had a reputation in the pueblo for being an excellent pottery-maker, if she could make full-scale examples for the museum of the polychrome ware. It was then that Maria and her husband, Julian (who painted the designs on the pottery after Maria shaped them), began an artistic collaboration that would last throughout their lives together.

Maria and Julian refined their pottery techniques and were asked to demonstrate their craft at several expositions, including the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, the 1914 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, and the 1934 Chicago World’s Fair. Part of their success came from their innovations in the style of black-on-black ware.

Although other pueblos, such as Santa Clara, had been producing black wares, Maria and Julian invented a technique that would allow for areas of the pottery to have a matte finish and other areas to be a glossy jet black. Through experimentation that began in 1919, they created a style that would become world famous.

Part of the unique-ness of San Ildefonso pottery is the clay that is used, which comes from their reservation. Dried clay and volcanic ash are collected yearly from selected locations throughout the reservation, and later combined with water in small batches. The clay from each pueblo has its own mineral composition, allowing for rich differences in texture and color. The watery clay slip that is used on the black wares, for example, has a rich iron content that turns black when fired in a particular way.

After a batch of clay is mixed and has set for a few days, a “pancake” of clay is formed and pressed into a puki, beginning the process of building a pot. The puki is a bowl-shaped form that supports the bottom of the pot as it is being built. Most commonly, pots are formed with a coil technique, in which long snake-shaped coils are circled around the base of the pot and blended together to create the walls of the vessel. A potter’s wheel is not used in traditional pueblo pottery making. When the height and the amount of clay are just right, the walls of the pot are smoothed and shaped into curves with pieces of gourd, called kajepes.

The pot is left to partially dry after the form is completed. In its semi-dried state, the pot is ready to be scraped, which refines the shape and removes any irregularity. Then the pot is sanded with sandpaper to rid it of any grit. The red slip is applied next, and the pot must be burnished with a stone before the slip dries completely. This step is most critical for the glossy nature of the black wares.

A decoration is painted onto the polished surface, resulting in matte areas once the piece is fired. Traditionally the men of the pueblo do the painting, but women were taught the process and painted during the times that the men had left the pueblo for work. Julian replicated and was inspired by many pre-historic designs. He was fond of many motifs, using ancient symbols in new combinations. He often painted the avanyu, the horned water serpent, which he saw as a symbol for the rush of water after a hard rain, and as a metaphor for the pueblo itself.

Black wares become so in the firing process. This labor-intensive task is done after many pots have been made, to maximize efficiency. Wood and dried cow manure are piled around an iron grill, upon which the pottery has been carefully stacked. The pile is lit and left to burn for a specified amount of time, until the fire has reached its maximum heat. At this time the fire is smothered with ash or fresh manure, producing a smoke-filled reducing atmosphere that turns the pots black. Variations in the process can produce pottery with black areas and red areas, which are also popular.

For many years, Maria and Julian produced their pottery together amid raising a family and carrying out traditional duties for the pueblo. Their children were taught the importance of the craft, and they participated in various ways. After Julian’s death in 1943, Maria began working with her daughter-in-law Santana. Santana provided the painted decoration that was her father-in-law’s legacy. After 1956, Maria also worked with her son Popovi Da. It was Popovi who helped market her work, building a shop at the pueblo and speaking about the pottery tradition of San Ildefonso at lectures across the country. One of the family’s most innovative potters is Maria’s grandson Tony Da (1940-2008). Tony combined sculptural techniques with traditional forms to create unique forms. Due to a motorcycle accident, Tony no longer makes pottery, but he continues to work as a painter. Many other family members and people from San Ildefonso continue to make pottery, carrying on the tradition so openly shared by Maria.

Maria signed her pieces several different ways over the course of her life, and to some extent, these signatures can help to date her work. At first, she signed her pots “Marie” because she was told that this name would be more familiar to those who would buy her work. Through the years her pieces were signed “Poh ve ka,” “Marie,” “Marie & Julian,” “Marie & Santana,” “Maria Poveka,” and “Maria/Popovi.”

Since her death in 1980, the pottery of Maria and her family has become increasingly more collectible and difficult to find. J. Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery continually searches the country for fine examples of her work.

[smart-photo background_color=”#ffffff” height=”40em” text_color=”#666666″ title=”true” title_expanded=”true” thumbnails_position=”bottom” transition=”fade_moveFromRight” thumb_width=”70″ thumb_height=”70″ transition_rows=”1″ slideshow_can_random=”false” tooltips=”true”]

[/smart-photo]