Richard Bresnahan directs a pottery studio on the campus of Saint John’s, a Benedictine abbey and university in the woodlands of central Minnesota. Originally from Casselton, North Dakota, where his father ran a grain-elevator company and his mother raised a family of six; Bresnahan (b. 1953) is unapologetic about his rural Midwestern roots.

At the same time, he harbors a fierce admiration for the frugality and inventiveness of hardworking farmers-folks who repair things when they break, fell trees and mill lumber, stockpile machine parts for reuse, card and spin wool, raise chickens, and grow and can their own food. “Every day I witnessed the rigors of an agrarian lifestyle,” he says, “and saw the interconnectedness of all things and the need to improvise and make do with what was at hand.”

Richard Bresnahan graduated from Saint John’s University in 1976, having studied with ceramics professor Bill Smith. While at Saint John’s, Bresnahan also took classes from Johanna Becker OSB, a member of Saint Benedict’s Monastery and a professor at its associated college in St. Joseph, Minnesota. A specialist in Japanese art, Sister Johanna wrote her dissertation on Karatsu ware, a type of stoneware first produced in the late 16th century by émigré Korean potters in northwest Kyushu. A meticulous scholar with an expansive knowledge of Asian ceramics, she soon became Bresnahan’s confidant and mentor, appraising his skills and helping him refine his analytical abilities.

Through her connections in Japan, Sister Johanna secured an apprenticeship for Bresnahan with Nakazato Takashi, a thirteenth generation potter in the seaside town of Karatsu. (Takashi was the son of Tarouemon XII, who was named a “Living National Treasure” during Bresnahan’s time with the family.) Bresnahan’s apprenticeship with the illustrious Nakazatos lasted nearly three-and-a-half years, and through them he absorbed the traditions, techniques, and reverence for clay that permeated every aspect of their daily lives.

Rather than ordering materials from a catalogue as he had done in Minnesota, he discovered that is was possible-even preferable-to excavate local clays and to wash away their inherent impurities. He also found out how to make glaze from ash and then how to apply the solution quickly and evenly to greenware.

As importantly, the Nakazatos encouraged Bresnahan to think critically about kiln design and to consider how certain structural alterations might induce better aesthetic results. “The verve of 16-hour days,” says Bresnahan, “and of doing everything from sweeping the floor and making tea to digging clay and building kilns provided me with a holistic approach… and a deep respect for indigenous systems.”

After returning to the United States in late 1978, Bresnahan decided to put his newly acquired knowledge and experience to good use. He accepted an invitation from Saint John’s president, Michael Blecker OSB, to become the school’s first artist-in-residence and to establish a pottery studio on campus. Next, he located a deposit of clay nearby and had 18,000 tons of it stockpiled behind Saint John’s Preparatory School.

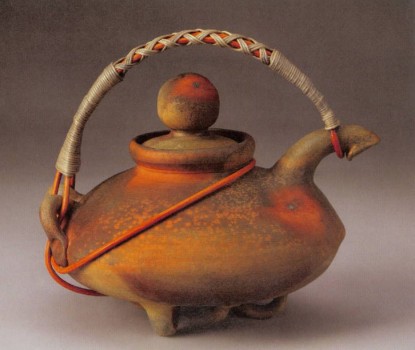

For his firings, Bresnahan collected deadfall and thinned trees from nearby forests, and for his glazes, ash from burned organic waste or discarded stone dust from local quarries. Sunflower hull ash, for example, produces a golden glaze, whereas navy-bean straw ash yields a milky white except when it pulls thin in the firing and blushes a vibrant blue. Combining flax-straw ash with granite dust creates a glossy dark temmoku (black), and ash from heating Bresnahan’s home makes still other hues: a soft azure blue from elm and a transparent caramel from oak.

Richard Bresnahan’s inaugural firing of the Johanna kiln, loaded with 8,000 pieces, occurred in October 1995. The stunning results became the focus of “First Fire,” a special exhibition the following year at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Since then, the kiln has been fired ten more times. The ten-day cycle requires round-the-clock attention, fifteen cords of wood, and the dedicated help of dozens of students, friends, past apprentices, and other volunteers.

Utilitarian wares-bowls, platters, cups, jars, teapots, and canisters-have long been Bresnahan’s mainstays, and this remains true today. But after nearly forty years as a potter, he continues to be enthralled with his craft and with experimenting with glaze ingredients, loading permutations, and various ceramic forms.

Indeed, an abiding respect for ecology and natural systems has always characterized Richard Bresnahan’s philosophy and his ongoing dialogue with fire and clay. Throughout his long career, he has consistently challenged himself to undertake new firing techniques, to test potential glaze materials, and to devise unique and elegant functional forms. As a result, the dynamic pottery Bresnahan creates reflects both the specifics of his physical environment-by utilizing local resources-and his own far-reaching artistic vision.

Dr. Matthew Welch, Deputy Director of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, “Stoked” (2010)

Website

http://www.csbsju.edu/pottery