Jim Scott was born in Los Angeles, California, but was raised in Texas on his father’s livestock farm. His attraction to art was evident at an early age, as was his preference for the out-of-doors. After a general college education and a tour in the Navy, Scott came to St. Louis, arriving on his 21st birthday. It was after dark when he reached the city and stopped under the Eads Bridge. Scott remembers the moment as a turning point in his subject matter, stating “Eads was fantastic. The river was romantic. I have always had a love for it since I saw it the first time.”

Scott was now determined to become a painter and began spending summers in Connecticut studying with Robert Brackman, remaining in St. Louis for the remainder of the year working with local artist Frank Nuderscher. During these early years, Scott worked in oil paints – the traditional and respected medium for professional artists. He attained a modest success, selling landscape paintings and portraits, but in 1963 he saw the work of English watercolorist Jack Merriott – then vice-president of the British Water Color Society – and was so inspired that he contacted the artist and spent the next three summers studying with him in England, Scotland and Wales. Since that time, Scott has worked almost exclusively in watercolors and remains dedicated to his art. As he puts it; “Painting is my all-consuming interest. I am more alive when I am working at it than at any other time.”

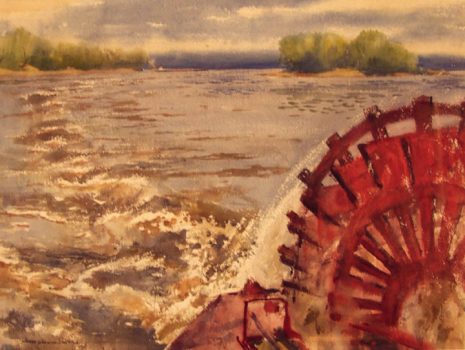

Even as a child, Scott was fascinated by Mark Twain’s stories of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer and their adventures on the Mississippi River, and although Scott has painted rural fields, city scenes and industrial landscapes, the River remains among his favorite subjects. In Shipyard, South St. Louis (ca. 1980) Scott combines the industrial with the idyllic in an image that transforms even the rough homely buildings of urban industry into graceful elements of a glowing river landscape. Conversely, in Paddlewheel (ca. 1970) Scott focuses primarily on the river and the rough water that results from the action of the paddlewheel – itself relegated to the corner of the composition. Yet even with this brief indication of the source of the agitated water, Scott has managed to remind us of the importance of this method of river travel that has left its mark on American history, just as the trail of turbulence reaches to the far distant horizon of the painting.

Website

http://www.jamesgodwinscott.com